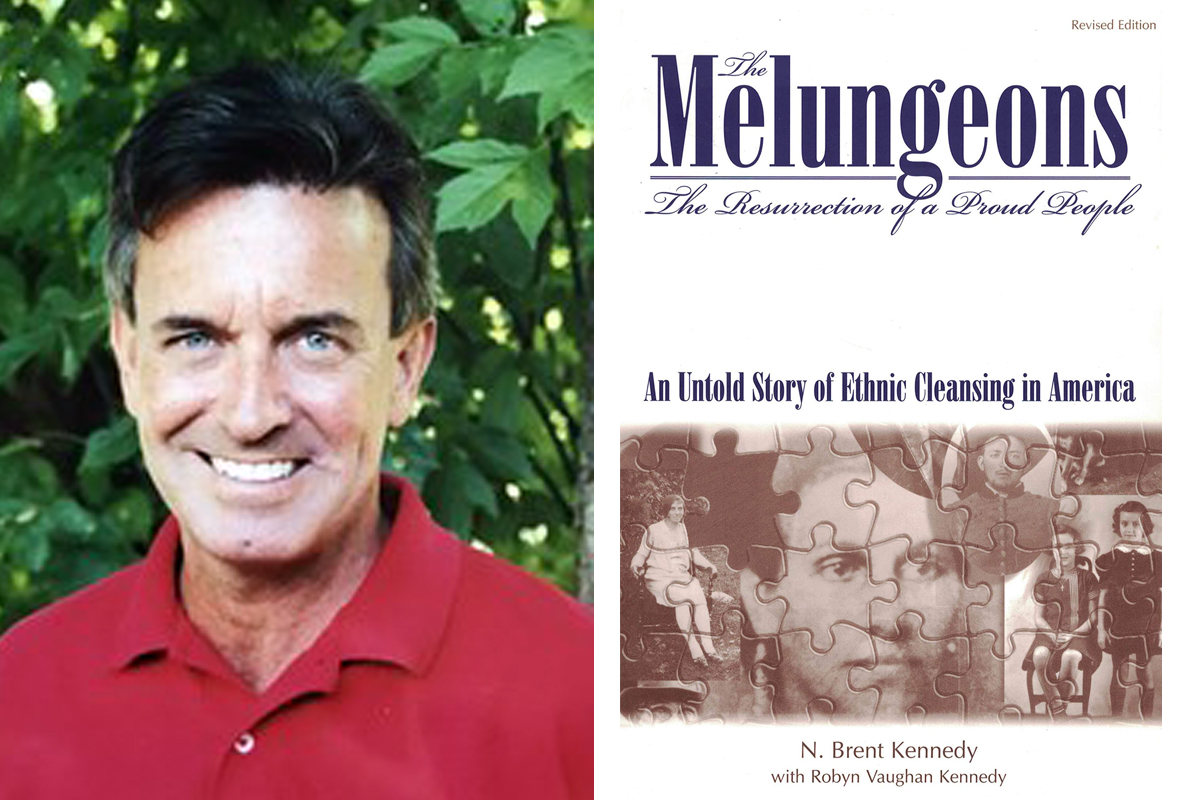

Dr. N. Brent Kennedy III, founder of the Melungeon Heritage Association (MHA), scholar on Melungeon ancestry, and author of the Melungeons: The Resurrection of a Proud People, passed away on September 21, 2020 in Wise, Virginia.

He was a great friend of Turkish people and Turkish heritage, led several delegations to Turkey and investigated the Turkish roots of the Melungeon community. He was the author of “The Melungeons: The Resurrection of a Proud People, 1996” and co-author with the late Joseph Scolnick of “From Anatolia to Appalachia: A Turkish-American Dialogue”. He was instrumental in the development of a sister city relationship between his home town of Wise,Virginia and Cesme, Turkey.

Dr. Kennedy was born in 1950 in Wise County, Virginia to Brent Kennedy and the late Nancy Kennedy. He graduated from Clinch Valley College (University of Virginia’s College at Wise) and held a doctorate from the University of Tennessee in Knoxville. Kennedy held various academic positions at Tusculum College, Tennessee; Mercer University, Georgia; University of Virginia’s College at Wise; and Georgetown University, Washington DC. He was also President of the Wellmont Foundation of Wellmont Health Systems.

He was the founding member of The Kennedy Brothers music group and has written numerous songs and screenplays.

In 2005, Dr. Brent suffered a stroke and had been hospitalized for over 10 months. He returned to his home in Kingsport, Tennessee in 2006 where he lived utill his death.

Brent Kennedy is survived by his wife, Robyn; his son, Ryan and his brother, Richard and many of his Melungeon brothers and sisters.

Assembly of Turkish American Associations express its deepest condolences to the Kennedy Family, members of the Melungeon Research Association and the Turkish American community.

A Meluncan Looks at Turkey

By Professor Dr. N. Brent Kennedy, Vice Chancellor, The University of Virginia’s College at Wise

Wise, Virginia, Summer, 1998

I admit that I am in love with Turkey. With her people, her land, and much of her history. My wife has forgiven this indiscretion, for she knows that I cannot help myself and she has consented to permit this other woman to coexist under our roof. I did not expect to fall in love. Yes, I knew prior to my first filming expedition that my people – the Melungeons (pronounced “muh-lun-junz”) of the Appalachian Mountains – were of probable Ottoman Turkish and sixteenth-century Portuguese/Moorish origins. But I had also grown up in a society where evil was personified by the Moor, the Turk, the so-called Infidel, and where Americans were told that the best that modern Turkey could offer was a society exemplified by the cruel but inept Turks of the 1960’s blockbuster film, “Lawrence of Arabia,” or, more recently, a supposedly true film highlighting a wretchedly unfair Turkish system of justice called “Midnight Express.” But I was compelled by some inward spirit to go see for myself the theoretical homeland of at least some of my ancestors. My friends advised me not to go, and then when it was clear that I would ignore them and go anyway, they insisted that I at least get all possible inoculations and, under no circumstances, drink the water or venture out at night lest I surely be murdered by some crazed Muslim zealot. I did visit my physician and endured all sorts of needles and pills, and I slept not one second on the long trip from Atlanta to New York to Zurich to Rome and, finally, to Istanbul (the reason for such an insane flight pattern is fodder for another story on another day!). But, when at long last I stepped off the plane, inexplicably all the doubts dissipated like a cloud of vapor. I could see it in the faces of the people who greeted me. In their physical features, their eyes, even their demeanor. I was home, and I knew it.

Three years and five more treks to Turkey later, not only the oral traditions among our people, but the genetics, the linguistics, and long ignored historical archival records substantiate the presence of Ottoman Turks in sixteenth-century Virginia and the Carolinas. They came as businessmen and traders to the colonies, textile workers and servants to both the English and the Spanish, and some were simply jettisoned as human cargo by Sir Francis Drake when he likely sat a hundred or more Levents off on the North Carolina coast in 1586. Unfortunate young men enslaved by their Spanish captors after some long forgotten Mediterranean battle and engaged in forced labor in the Caribbean until Drake, by chance or maybe Divine intervention, attacked the stronghold where they were kept. And though they undoubtedly wanted to return home, reunion with their loved ones was not their destiny. Instead, they were abandoned here, intermarried with Native Americans, and later again with Europeans. Through intermarriage or through surname adoption, they took on names such as Kennedy, Nash, Mullins, Collins, Osborne, Goins, Hall, Ramsey, Alley, Reece, Sexton, and Moore. They did everything they could to blend in, for melding was the only way to survive. And amazingly, significant parts of their cultural and genetic nature survived as well, despite the overwhelming Anglo effort to stamp out every thread of evidence. It’s why some of us Melungeons – supposedly just “dark” Englishmen – have sarcoidosis, thallasemia, Behcet’s Disease, Familial Mediterranean Fever, and Machado-Joseph Disease. It’s why many of us are lactose intolerant, have central Asian shovel teeth, the so-called “Central Asian cranial bump or ridge,” and Siberian cerumen. It’s why 177 Melungeon blood samples analyzed by Dr. James Guthrie in a published gene frequency study, showed no significant differences between Melungeons and populations from the Galician Mountains of Portugal and Spain, Libya, Malta, Cyprus, the Levant coast, and northern Syria. It’s why, during my first trip, people who didn’t know I was an American addressed me in Turkish. And maybe it’s also why hundreds of words from both the Melungeons and related southeastern Native American tribes, have identical counterparts in Ottoman period Turkish – the old Melungeons called a watch a “saats”, the Cherokee word for “mother” or “woman” is “Ana – ta” and the Cherokee word for “father” or “supreme chief” is “Atta.” The Creek Indian word for Holy Man is “Hadjo,” and our old folks thanked their cows and goats when milking them by saying “Sag” (pronounced “sow” in the Appalachian dialect). And the list goes on and on. No, these are surely not accidents and I, and other Melungeons, know that. Even our name, long a mystery to the Anglos, suddenly makes sense if one considers a possible Turkish and/or Arabic origin (and Ottoman Turkish was, of course, a blending of Turkish, Arabic, and Persian). For a people abandoned in a new and threatening world, never seeing their families again, denied the rights to vote, to go to school, to own land, or to hold a job, and ridiculed when trying to claim their true origin, the term “melun can” -“cursed soul” in both Turkish and Arabic- needs no further explanation. Yes, my ancestors were indeed “meluncanlar.”

But the story need no longer be a sad one. There is a beautiful lesson here, a powerful message that God set into motion four hundred years ago and is now, at long last, being delivered. What was a horrible story for those Ottoman immigrants has now turned into an inspired mission – a mission that would have been impossible had these sad circumstances never occurred. For today, we Melungeons can serve as the linkage between the Old and the New, the East and the West, the Parent and the Child. We Melungeons can serve as the glue to tie all people of Central Asian origin together. No longer does the Turkic story stop in the West at Istanbul or in the East in Siberia – instead, it spins its history across both the Bering Strait and the Atlantic Ocean, at last completely encircling the globe. This reality is not new, but the recent recognition of it is indeed staggering in its implications. And it begs for continued academic study and personal introspection. Such introspection has occupied much of my private time. And I believe some of my thoughts – thoughts mirrored by other Melungeons as well – should perhaps be shared with modern Turks. Not that we Melungeons know Turkey better than present day Turks, nor do we, an Ocean away, necessarily know what’s best for Turkey. As Americans, we struggle like everyone else just to figure out what’s best for our own Nation. But we Melungeons do perhaps have a fresh view of Turkey – and Turks – that no other population on Earth possesses. We view Turkey as an orphaned child might view its Mother or Father after growing up alone and then enduring a lifelong journey to locate that missing parent. While we are proud Americans dedicated to our Nation, we are also captivated by the prospects of re-establishing a family bond with our parent. What orphaned child doesn’t dream of such a reunion? And it is this unique circumstance from which I write.

So, as a Melungeon, what it is that I would say to a Turk in Turkey?

First, I would say that our histories are not so different, despite 400 years of separation. The Appalachian people in general have always been a rugged, independent, proud mountain people recognized for their indomitable spirit, their superior bravery and skill as soldiers, their skill as artisans, for their family cohesiveness, and, yes, for their different culture when compared to other Euro-American populations. We have always been a people seemingly surrounded by enemies, disparaged, misunderstood, feared, and all the while alternately demanding and begging the outside world for acceptance. These characteristics have perhaps contributed to the self-sufficient nature of our Appalachian people. And, I believe, made us so much like the Turks who have suffered the same indignities. How wise of God, to separate us but still give us a common experience so that, even four centuries later, we are still culturally and psychologically the same people.

Second, I would also say to my Turkish brothers and sisters, that for we Melungeons who have struggled so hard to reclaim our heritage and our kinship, the thought of modern Turks taking for granted the ties that bind them together is inconceivable, even deplorable. Must you, like us, lose your sense of self before appreciating it? I always encourage those young Turkish students in the USA to study hard but to return home if possible and apply their skills and intellect to building a stronger Turkey. I feel like crying when I hear a young German whose mother is a Turk, deny his Turkish heritage. That is precisely what we did and four centuries could not erase the high cost of denying our very selves. What has the past taught us? We Melungeons can teach a valuable lesson to all these young people on the terrible price paid when one is forced to surrender his or her identity to find acceptance. I implore my Turkish brothers and sisters to put aside any petty differences and to work together to build not only a stronger, more industrialized, and economically sound Turkey, but to remain committed to both democracy and universal human rights.

Third, it would appear to be time for a Central Asian confederation that not only celebrates across common borders its shared culture and heritage, but that is unequivocally dedicated to bettering the lives of its citizenry, especially the poor and disenfranchised. No single Turkish ethnic subgroup can be superior to another, nor to any other human group, and indeed this guarantee is the theoretical cornerstone of modern Turkish freedom. As an example, after 400 years of intermarriage, we Melungeons now share many diverse heritages, ranging from Ottoman Turks, Jews, and Moors, to Native Americans, Africans, and Europeans. Our original population has spread into all American racial and ethnic groups, so much so that our tribal creed is now “Melungeons: One People, All Colors.” And this is our greatest strength as a population. Even Melungeons are Americans first, and then and only then, Melungeons. When Professor Türker Özdoğan and I attended the Turkic World Economic Congress in İzmir (at the invitation of Professor Dr. Turan Yazgan) last summer, I noted with delight that the various Turkic representatives came in all sizes, shapes, and colors. Whether their skin was a beautiful ebony shade, a lovely ivory cast, or a captivating olive or red, the pride of a Turkic heritage was always there! I met Muslim Turks, Christian Turks, Jewish Turks, Buddhist Turks, Shaman Turks, and just Turks. This Turkic kinship crosses all national, theological, and so-called ethnic and racial boundaries, with the key to membership lying not in physical phenotype but simply within the heart of each human being. I can tell you that here in America if one feels himself or herself to be a Melungeon descendant and is willing to declare it publicly regardless of prejudices, then he or she is a Melungeon. Based on Atatürk’s philosophy, I would assume as well that if one feels himself or herself to be a Turk, then one is indeed a Turk, regardless of national origin or residence. And if this is indeed true, then the heart of pan-Turkism must correspondingly be “Turks: One People…Many Nations.”

Fourth, related to the above, a non-militant, non-nationalistic form of pan-Turkism is indeed in order, even mandated by recent events. I recognize the challenges of unifying populations with well-defined common interests but complicated by well-defined national borders. It is possible for neighbors and friends to join hands and hearts in common cause without moving into the same house. Just as the European nations feel compelled to unite with others of like mind and culture, and the Latin World feels drawn to a Pan American Union, and just as the Arab world longs for a similar union, so are Turkic peoples drawn by the same dream. Especially when the effort to be a part of another union has been repeatedly rebuffed. Like most Turks I, too, was praying that the EU would welcome Turkey into its fold with open arms. I thought this would be good for Turkey both economically and politically. But that didn’t happen, and frankly I don’t think it is apt to happen over the next eight to ten years, at least not in the unencumbered way that Turks would prefer. And now, as with my abandoned ancestors, I’m not so sure that Divine providence didn’t step in once again on Turkey’s behalf. Most gifts from God must be suffered through before the real meaning and value is understood. I came to understand my heritage through a life threatening illness, but in retrospect it was that very “misfortune” which led me to illumination. Turkey’s rejection by the EU is Europe’s loss, not Turkey’s, and time will show this to be the case. Turkey borders the most volatile region of the world and it’s only a matter of time until the “West” truly recognizes Turkey’s geopolitical value and comes to appreciate her long-standing, but equally undervalued contributions to stability in the region. But there is a wonderful gift clothed in this rejection, a gift well understood by many Melungeons. We, too, frantically sought full assimilation and acceptance by early Anglo-Americans, but it never really came. And because it never came, much of our cultural memory survived and – even four centuries later – has spurred us to reconnect with our family. What seemed to be an utter and total rejection by those around us was instead a great gift from God. Turkey has just received such a gift. With an increased emphasis on Central Asian, Siberian, and Caucasian linkages, coupled with increasingly stronger bonds with the United States and Israel, the inevitable benefits that will accrue to Turkey will more than compensate for Europe’s short-sightedness.

Fifth, and final, we Melungeons are proud to possess Turkish heritage, just as we are proud of the blood of every other nationality or race that flows through our veins. For some of us, the Anglo genes have captured our spirits, for others the Native American, or the African American, or the Portuguese, or simply the “American.” And this is perfectly acceptable since we are unified by a common heritage and cultural origin, but liberated by the diversity that followed due to intermarriage as well as our individual freedom to celebrate whatever it may be about ourselves or our culture or our history that most pleases or intrigues us. For me, it is undeniable: I am a “cultural Turk,” a blending of central Asia and the Mediterranean. And I always have been a cultural Turk, even before I knew the truth of who I was genetically. My central Asian anthropological characteristics, as well as my sarcoidosis and Familial Mediterranean Fever, simply confirmed physically what I already knew spiritually. And there are others like me. Others who instinctively think in the same way as Turks, react to certain music and food in the same way, and cannot help but show our emotions even if it means embracing our dearest male friends in a most non-northern European manner! This is who we are – and who we were – even before discovering the reasons why. Those Turks who have visited our small Town have invariably commented on how much they felt at home. Of how similar our customs and our culture seemed to be. The undeniable connections are there. Blood is indeed thicker than water. And for many Melungeons, it is Turkish – that is, Central Asian and Mediterranean – blood that pulls us eastward.

Our journey of discovery is not yet finished and, indeed, is likely to never be totally completed. At least I hope not, for it is the journey that teaches us what we need to know: what it is to be a Melungeon, or a Turk, or a human being of any complexion or origin. By more fully understanding my own true origins, I not only feel my spiritual connectedness to Turks, but to every other human being, from Native Americans and Africans, to Arabs and Jews, to Greeks and Armenians. They are all my brothers and sisters. Being a “Melungeon” or a “Turk” means being a true citizen of the World, culturally and genetically, and thus we are spiritual siblings to ALL other human beings. To re-visit the circumstances of those abandoned sixteenth-century Ottoman Levents, did not they themselves represent all creeds and colors but still were “Turks” nevertheless? And were they not sailing together under Barbarosa’s remarkable flag of religious tolerance – a naval banner combining the Muslim Star and Crescent, the Christian Cross, and the Jewish Star of David? By once again recognizing this undeniable kinship are we not coming full circle to the timeworn truth that we are all God’s children? If we are willing to hear it, the answer is yes. By discovering my Turkish roots, I am now, more than before, a human being whose kinship does – and indeed must – touch all other human beings. For me, it can be no other way. My mission is to ensure that the Melungeon story is told again and again, and that through its telling ALL people might learn something about their unseen human kinships, about kindness and mercy, and most certainly about justice. No injustice can be buried or ignored, whether committed upon or by a Melungeon, or upon or by a Turk. At some point every deed – good or bad – will see the light of day. Four hundred years and all the ethnic prejudice and racial laws our early Republic could muster could not suppress the eventual telling of our story. It was the search for truth that brought me, and other Melungeons back to our roots and such searches will forever more be indispensable to us as a people. And it is this continuing search for truth that will pull Turks and Melungeons – and thus Turkey and the United States – even more closely together. I give thanks to God for permitting me to learn a fuller truth about who I am, and for the wonderful friends He has brought my way, and for the challenges and tests He has used – and continues to use – to prod me along my path. I look forward to this continuing odyssey with the confidence that for both Melungeons and Turks – and indeed, all human beings – a new dawn is at hand.